4.4: Monopolistic Competition and Oligopoly

ECON 306 · Microeconomic Analysis · Fall 2019

Ryan Safner

Assistant Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/microf19

microF19.classes.ryansafner.com

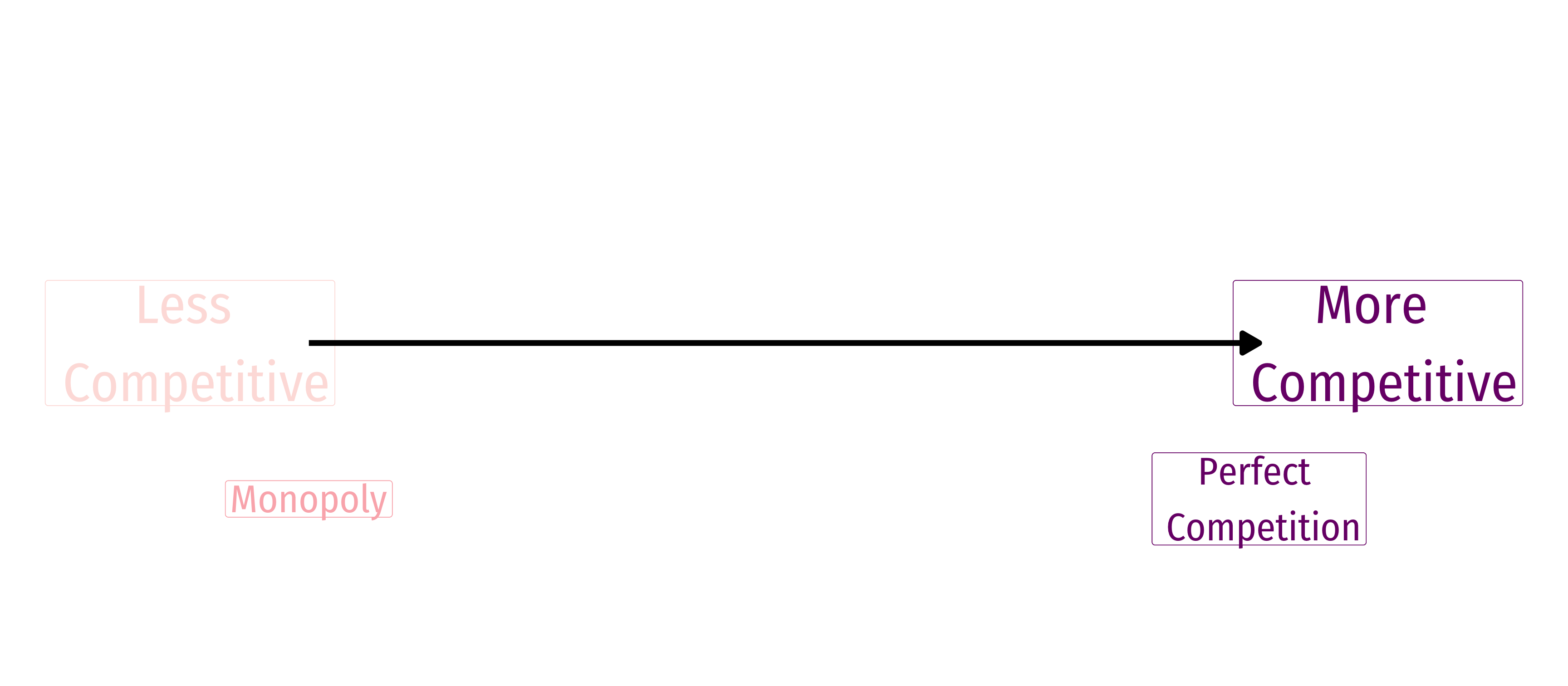

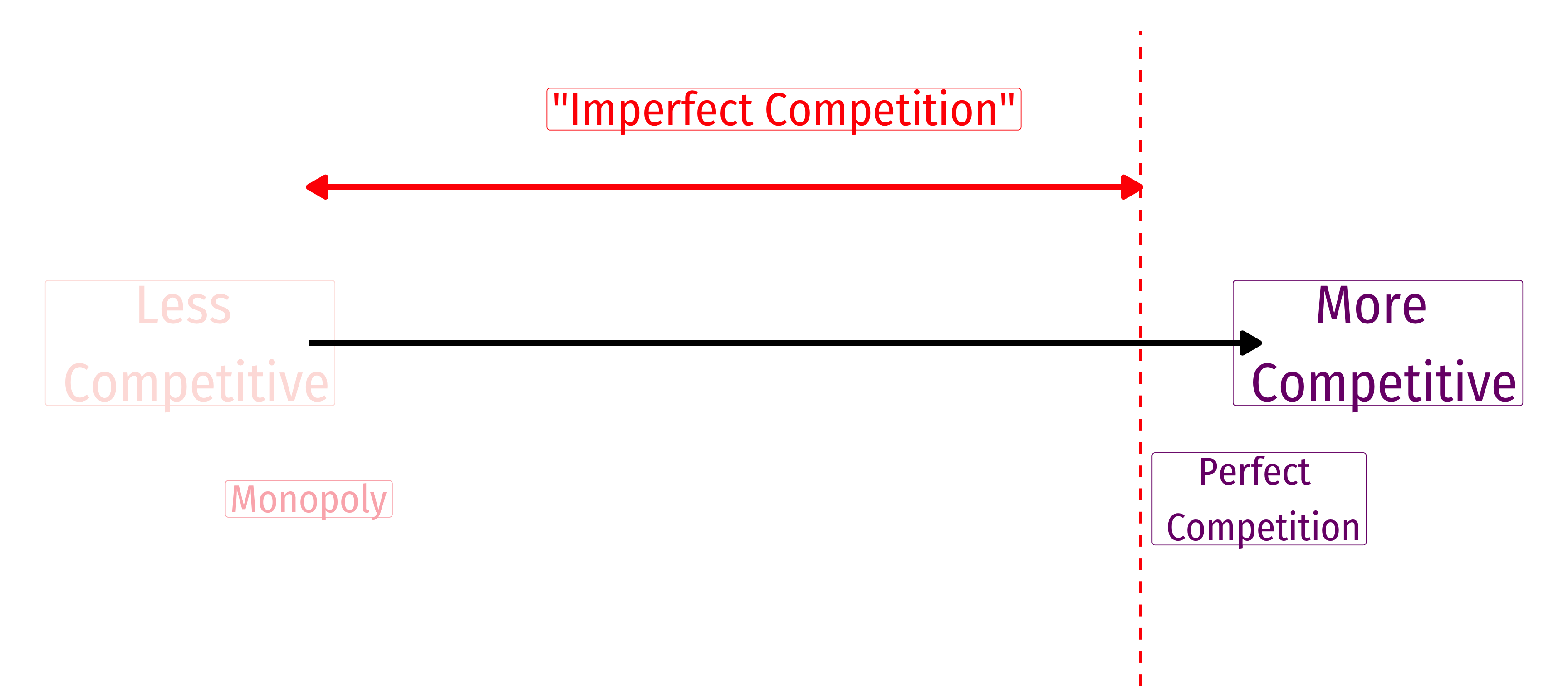

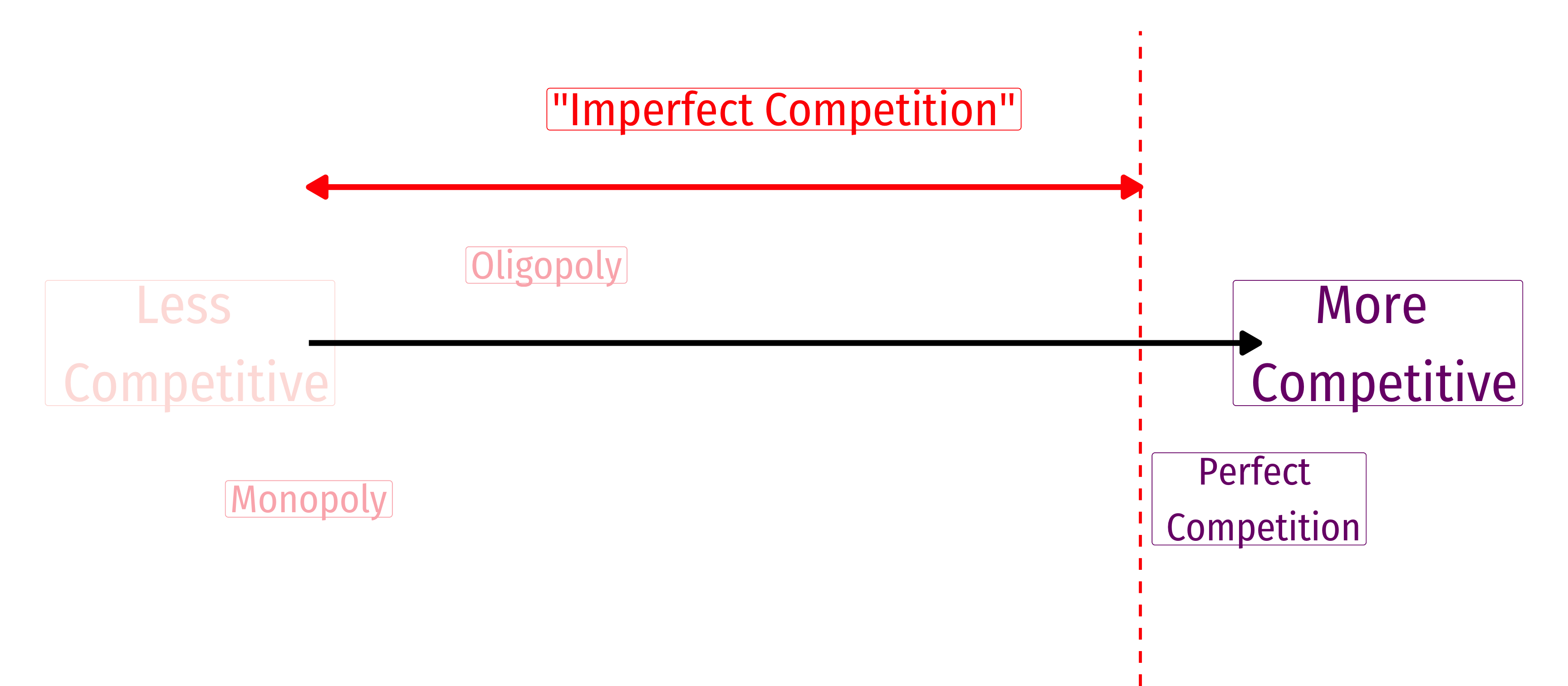

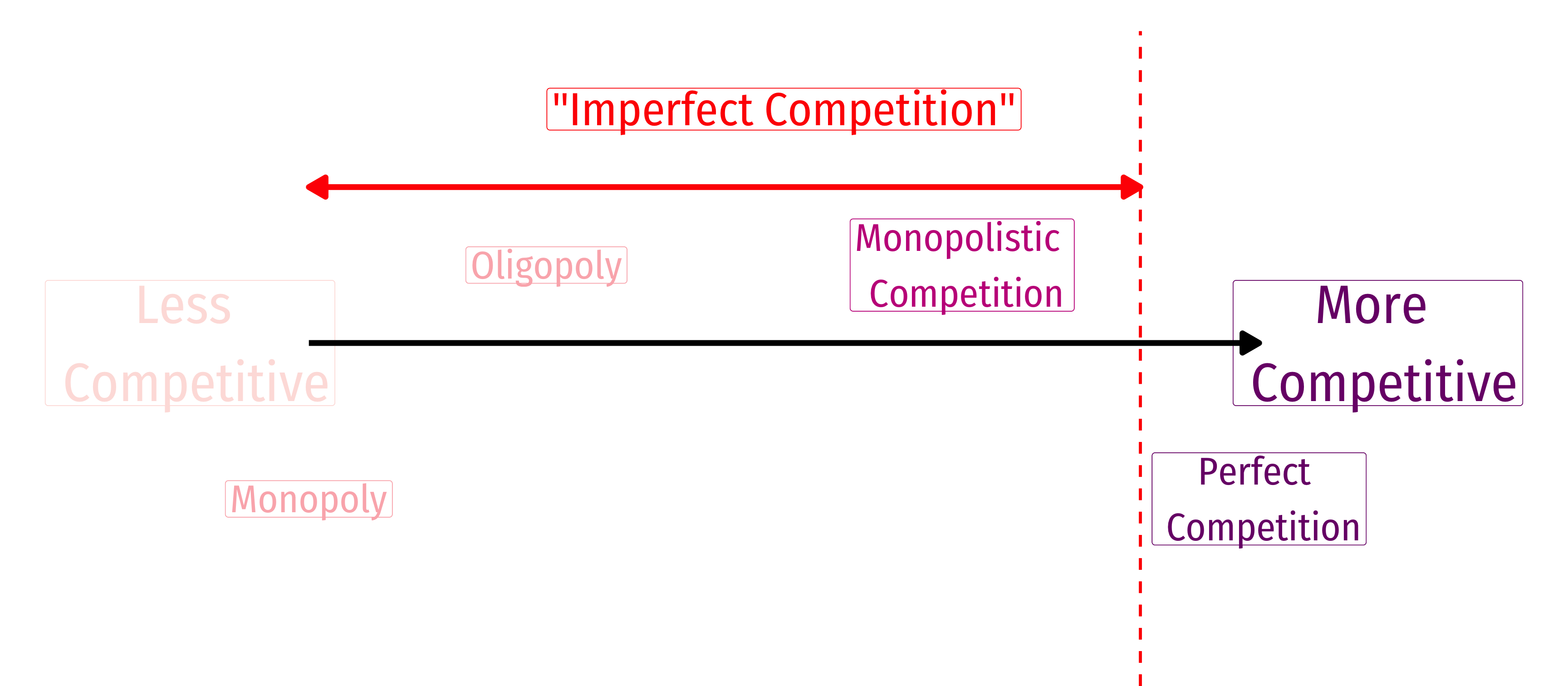

Imperfect Competition

Imperfect Competition

Imperfect Competition

Imperfect Competition

Imperfect Competition

Monopolistic Competition

Monopolistic Competition

- Monopolistic competition: hybrid of monopoly and competition, where each firm has some market power

Goods are imperfect substitutes

- consumers recognize non-price differences between sellers' goods

Entry and exit are free

- no barriers to entry

Each firm is a price-searcher

- faces own downward-sloping demand curve

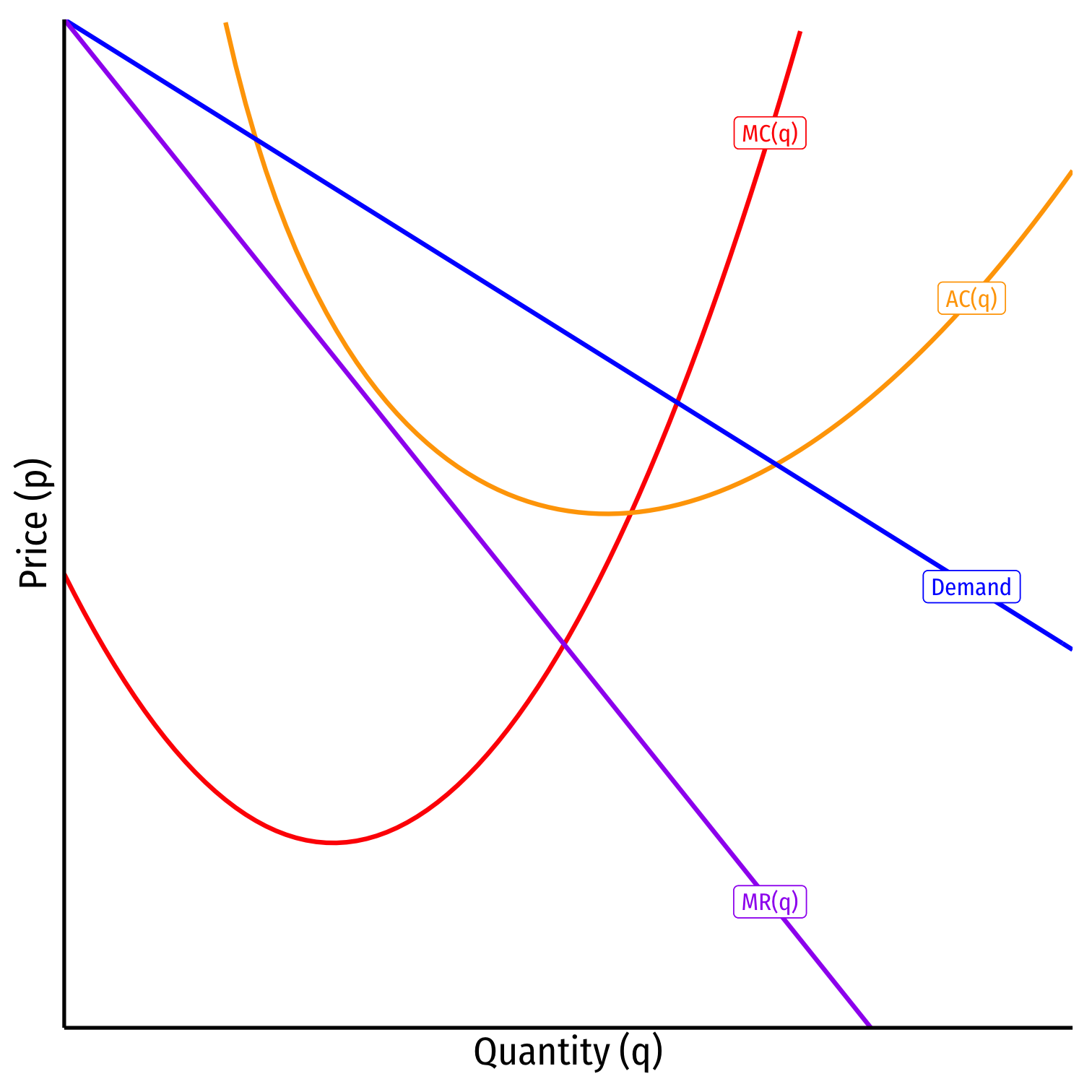

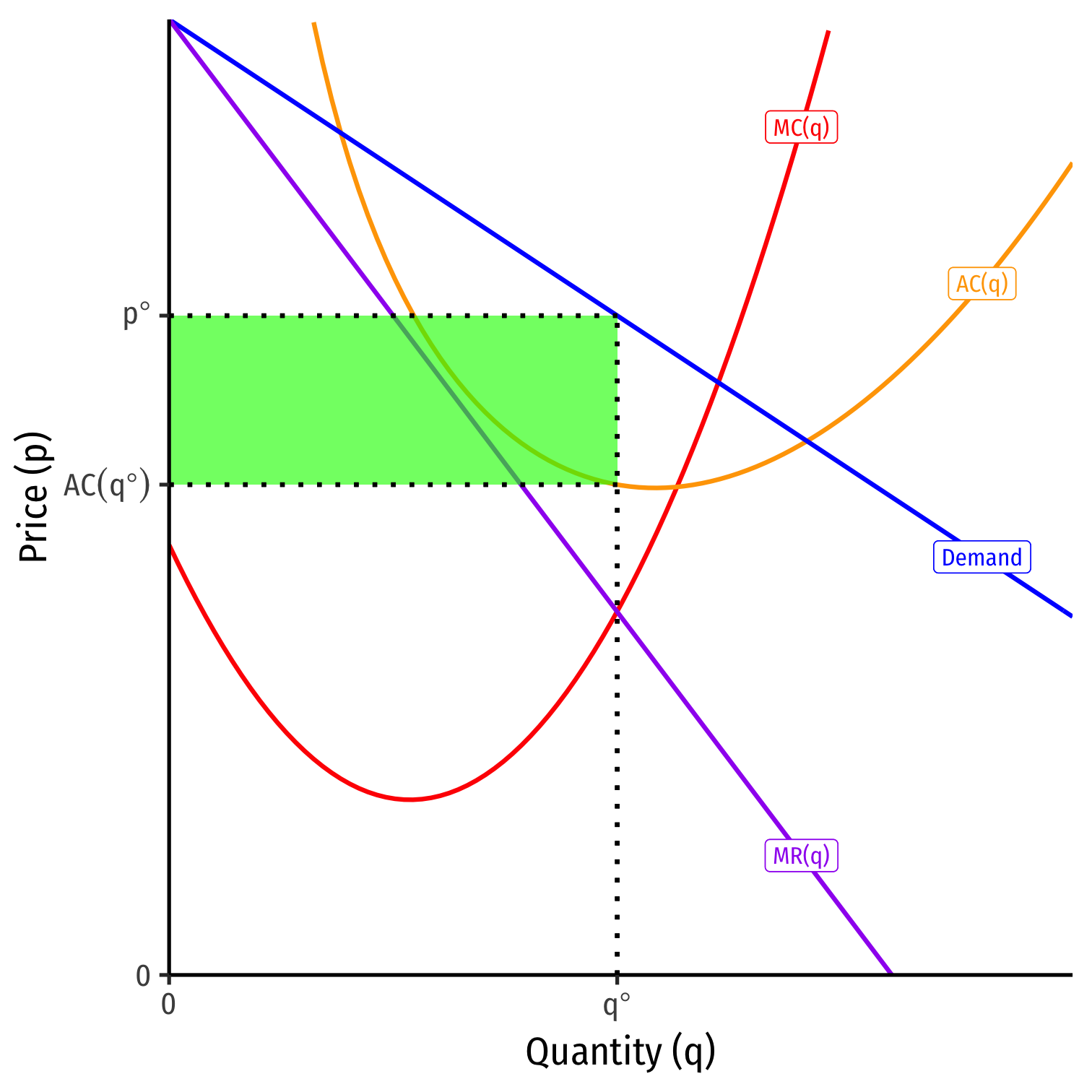

Monopolistic Competition Model: Short Run

- Short Run: Firm acts as a monopolist

Monopolistic Competition Model: Short Run

Short Run: Firm acts as a monopolist:

q∗: where MR(q)=MC(q)

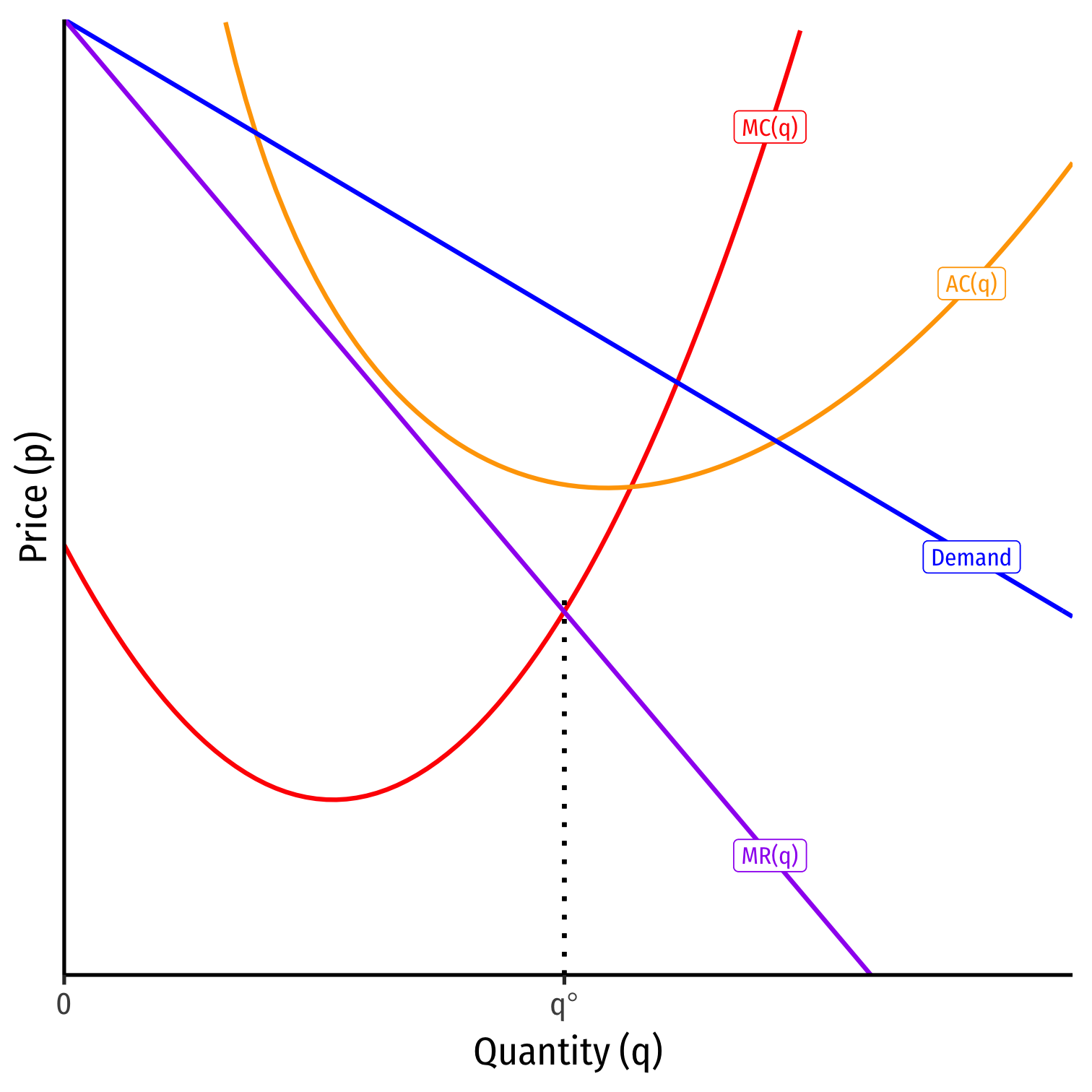

Monopolistic Competition Model: Short Run

Short Run: Firm acts as a monopolist:

q∗: where MR(q)=MC(q)

- p∗: at market demand for q∗

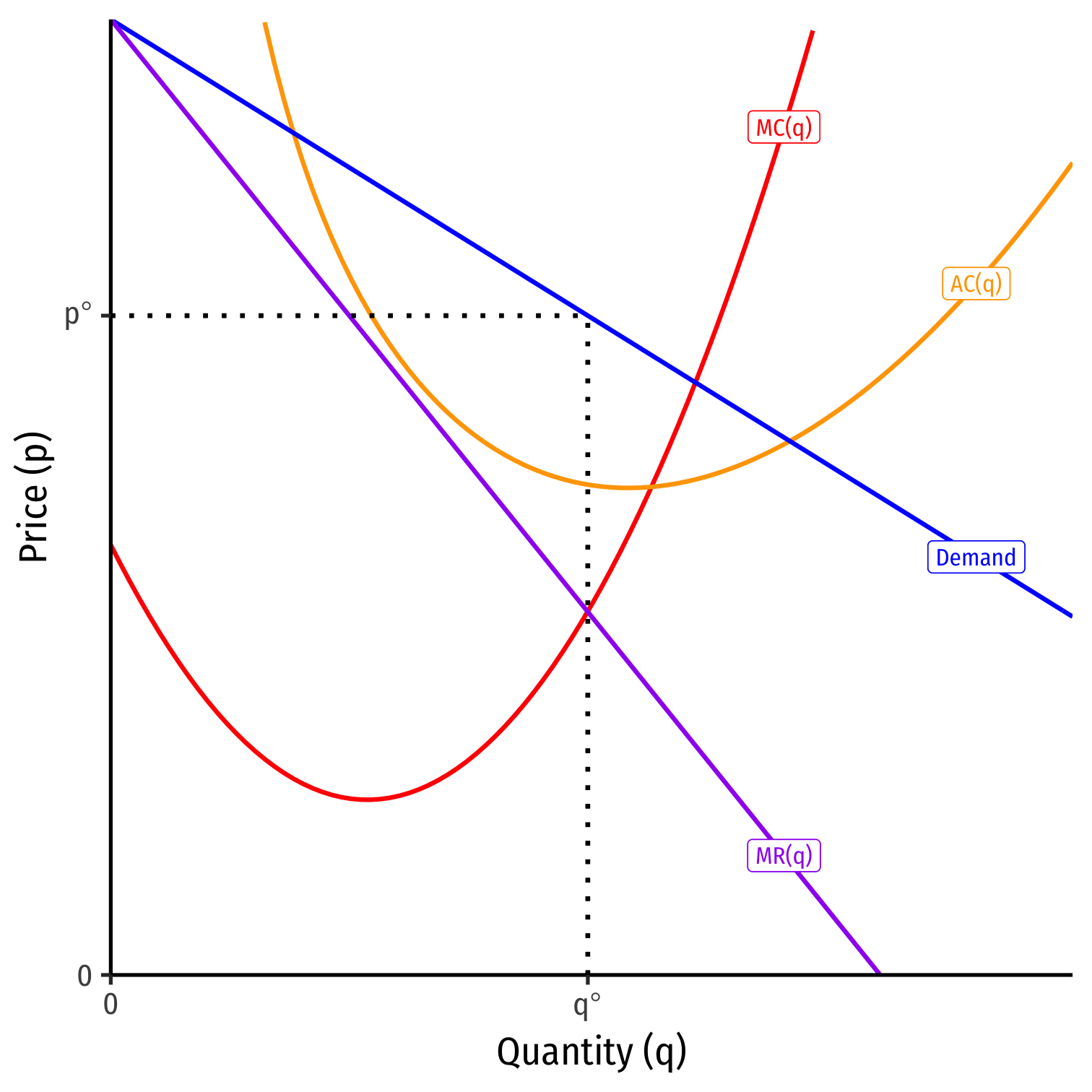

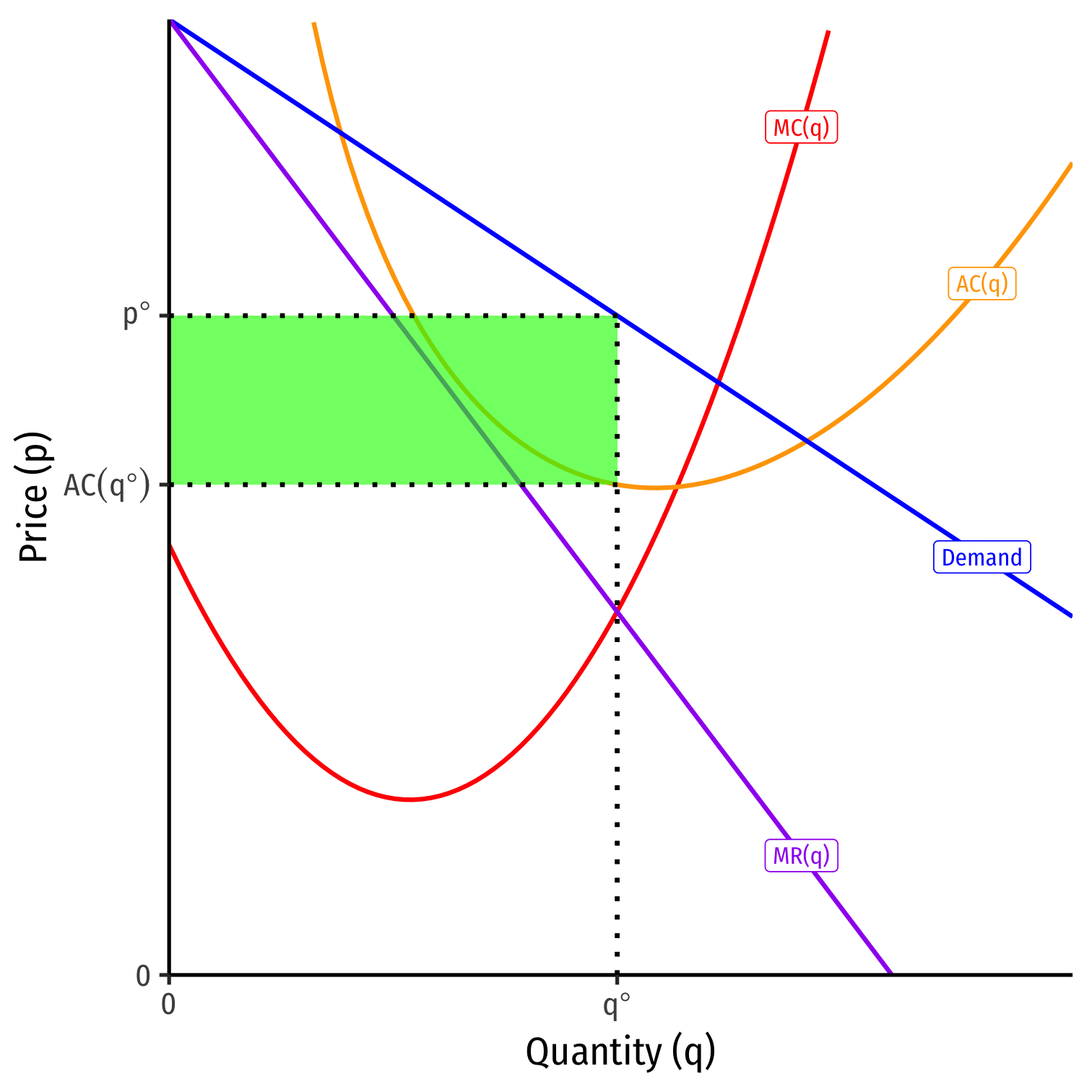

Monopolistic Competition Model: Short Run

Short Run: Firm acts as a monopolist:

q∗: where MR(q)=MC(q)

- p∗: at market demand for q∗

- Earns π=[p∗−AC(q∗)]q∗

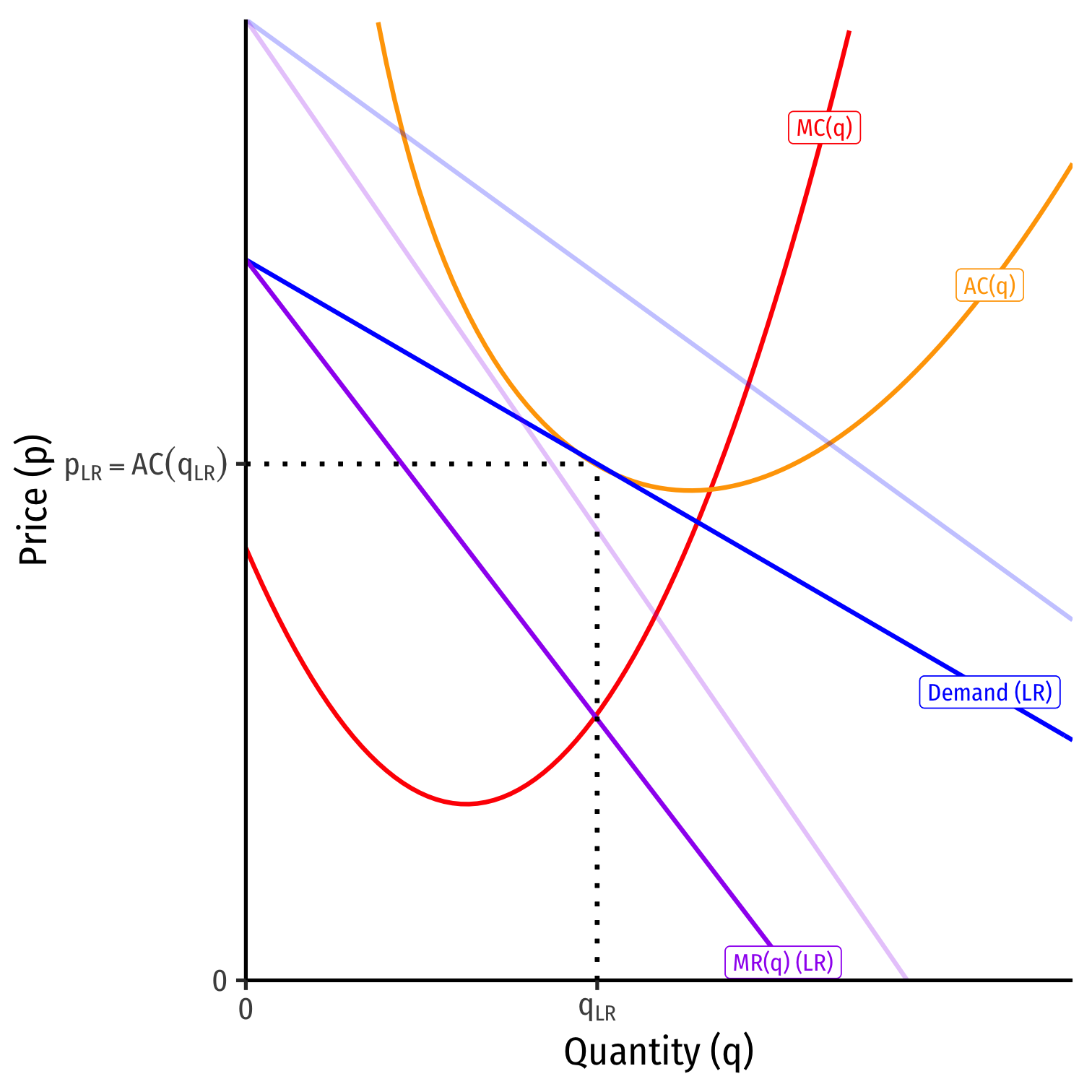

Monopolistic Competition Model: Long Run

Long Run: market becomes competitive (no barriers to entry!)

π>0 attracts entry into industry

Demand for each firm's product will decrease (and become more elastic), until...

Monopolistic Competition Model: Long Run

Long Run: market becomes competitive (no barriers to entry!)

π>0 attracts entry into industry

Demand for each firm's product will decrease (and become more elastic), until...

Long run equilibrium: firms earn π=0 where p=AC(q)1

1 Note: not necessarily the minimum of (AC(q))! (q) is determined by (MR) and (MC), not demand!

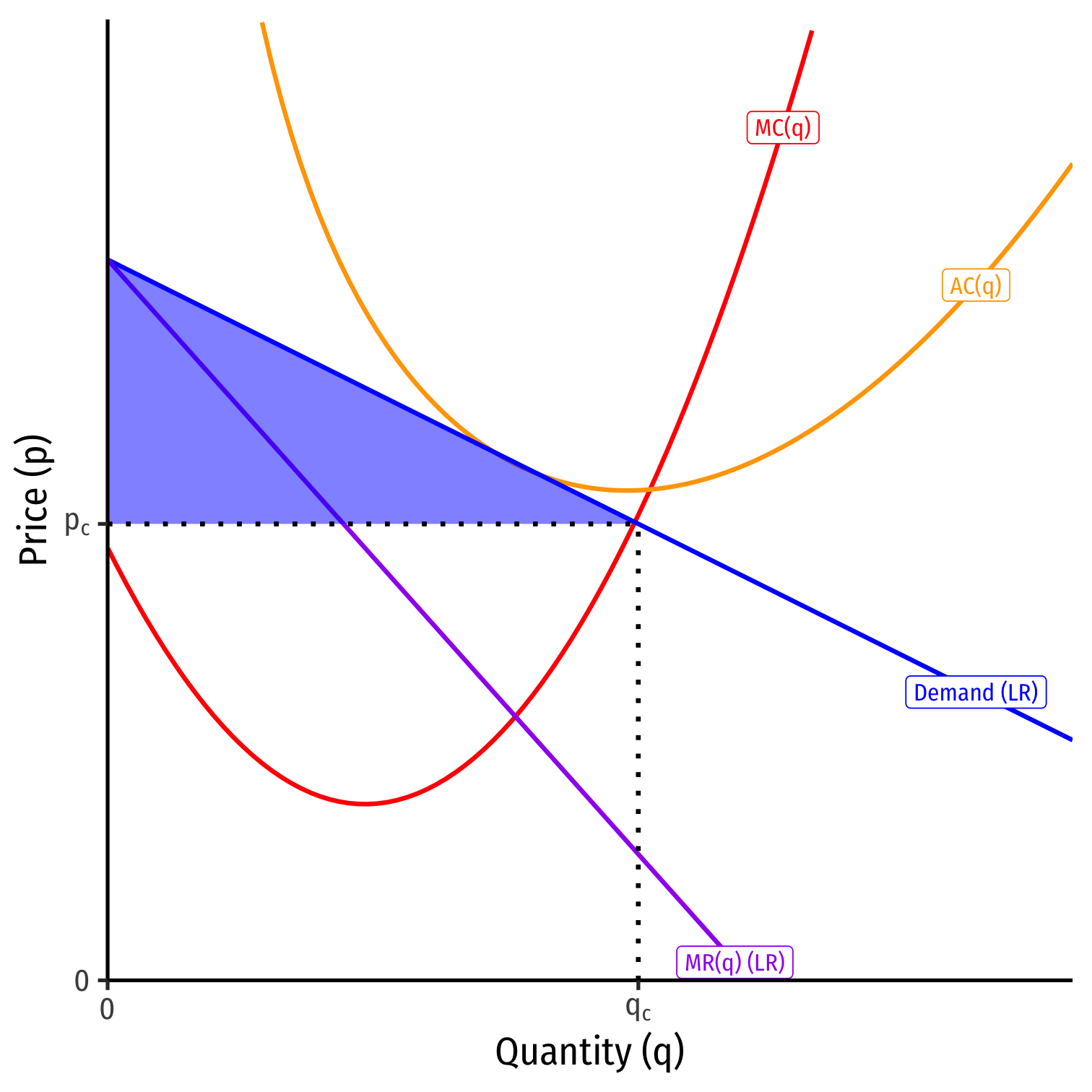

Monopolistic Competition vs. Perfect Competition

- Perfect competition (qc,pc)

- pc=MC(q)

- qc where P=MC(q)

- Maximum consumer surplus

Monopolistic Competition vs. Perfect Competition

Perfect competition (qc,pc)

- pc=MC(q), allocatively efficient

- qc where P=MC(q)

- Maximum consumer surplus

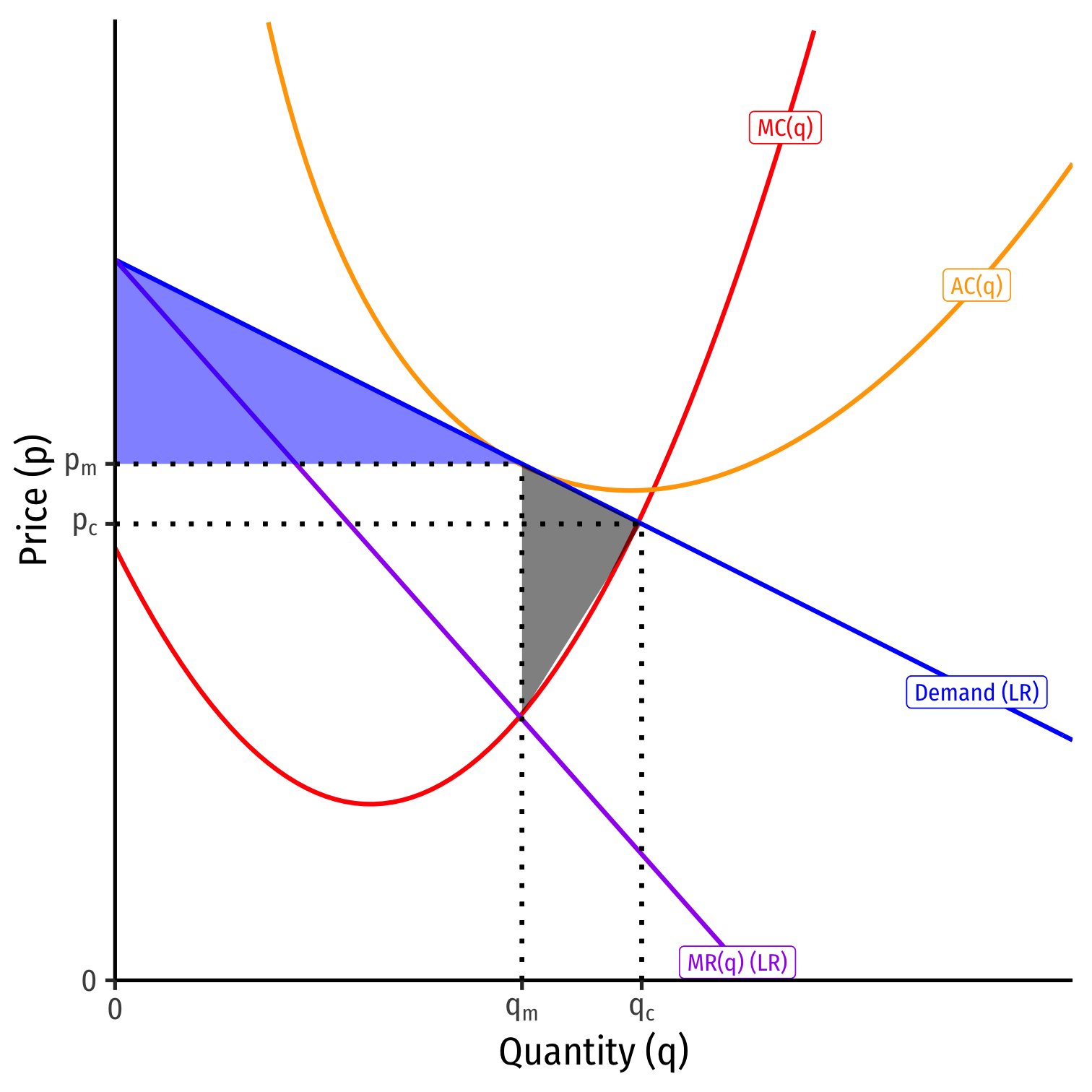

Monopolistic competition (qc,pc)

- pm=AC(q)

- pm>MC(q), allocatively inefficient

- qm<qc, where MR(q)=MC(q)

Like a monopolist, produces less q at a higher p than competition

- Less consumer surplus

- Now deadweight loss

Like perfect competition, still no π in the long run!

Oligopoly

Oligopoly

Oligopoly: industry with a few large sellers with market power

Other features can vary

- May sell similar or different goods

- May be some barriers to entry or none

Key: Firms make strategic choices, interdependent on one another

For modeling simplicity:

- Duopoly: a market with only two sellers; Triopoly: 3 sellers, etc.

Oligopoly: Modelling

Unlike PC or monopoly, no single "theory of oligopoly"

Depends heavily on assumptions made about interactions and choice variables

One certainty: oligopoly is a strategic interaction between few firms (i.e. ideal for game theory)

Game Theory

- Game theory: a set of tools that model strategic interactions ("games") between rational players, 3 elements:

- Players

- Strategies that players can choose from

- Payoffs to each player that are jointly-determined from combination of all players' strategies

Game Theory vs. Decision Theory Models I

Traditional economic models are often called Decision theory:

Optimization models ignore all other agents and just focus on how can you maximize your objective within your constraints

- Other agents are a primary cause of your constraints - but not considered in the model!

- Consumers max utility; firms max profit, etc.

Outcome: optimum: decision where you have no better alternatives

Game Theory vs. Decision Theory Models I

Traditional economic models are often called Decision theory:

Equilibrium models assume that there are so many agents that no agent's decision can affect the outcome

- Perfect competition - firms are price-takers, etc

- Alternatively: monopoly/monopsony: the only buyer or seller

- Regardless: ignores all other agents' decisions!

Outcome: equilibrium: where nobody has no better alternatives

Game Theory vs. Decision Theory Models III

Game theory models directly confront strategic interactions between players

- How each player would respond to a strategy chosen by other player(s)

- Lead to a stable outcome where everyone has considered and chosen their best responses

Outcome: Nash equilibrium: where nobody has a better strategy given the strategies everyone else is playing

Equilibrium in Oligopoly

What does "equilibrium" mean in an oligopoly?

In competition or monopoly, a vector of (q∗,p∗) for whole market such that no firms/consumers have incentives to change price

Oligopoly: we can use game-theoretic Nash Equilibrium:

- no player wants to change their strategy given all other player' strategies

- each player is playing a best response against other players' strategies

As a Prisoner's Dilemma I

Suppose we have a duopoly between Apple and Google

Each is planning to launch a new tablet, and choose to sell it at a High Price or a Low Price

Payoff matrix represents profits to each firm

- First number in each box goes to Row player (Apple)

- Second number in each box goes to Column player (Google)

Google |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| High Price | Low Price | ||

| Apple | High Price | 500, 500 | 250, 750 |

| Low Price | 750, 250 | 300, 300 | |

As a Prisoner's Dilemma II

- From Apple's perspective:

- Low Price is a dominant strategy for Apple

Google |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| High Price | Low Price | ||

| Apple | High Price | 500, 500 | 250, 750 |

| Low Price | 750, 250 | 300, 300 | |

As a Prisoner's Dilemma II

From Apple's perspective:

- Low Price is a dominant strategy for Apple

From Google's perspective:

- Low Price is a dominant strategy for Google

Google |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| High Price | Low Price | ||

| Apple | High Price | 500, 500 | 250, 750 |

| Low Price | 750, 250 | 300, 300 | |

As a Prisoner's Dilemma II

- Nash equilibrium: (Low Price, Low Price)

Google |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| High Price | Low Price | ||

| Apple | High Price | 500, 500 | 250, 750 |

| Low Price | 750, 250 | 300, 300 | |

As a Prisoner's Dilemma III

Nash equilibrium: (Low Price, Low Price)

A possible Pareto improvement: (High Price, High Price)

- Is it a Nash Equilibrium?

Google |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| High Price | Low Price | ||

| Apple | High Price | 500, 500 | 250, 750 |

| Low Price | 750, 250 | 300, 300 | |

As a Prisoner's Dilemma IV

Google and Apple could collude with one another and agree to both raise prices

Cartel: group of sellers coordinate to raise prices to act like a collective monopoly and split the profits

Instability of Cartels

Cartels often unstable:

Incentive for each member to cheat is too strong

Entrants (non-cartel members) can threaten lower prices

Difficult to monitor whether firms are upholding agreement

Cartels are illegal, must be discrete

Government-Sanctioned Cartels I

Like monopolies, some cartels exist because they are supported by governments or regulators, possibly by rent-seeking

National Recovery Administration (1933-1935)

- cartelized most industries to artificially raise prices of goods

- found unconstitutional in Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States (1935)

Government-Sanctioned Cartels II

Source: NPR Planet Money

"Marvin Horne was known as the raisin outlaw. His crime: Selling 100% of his raisin crop, against the wishes of the Raisin Administrative Committee, a group of farmers that regulates the national raisin supply. He took the case all the way to the Supreme Court, which issued its final ruling this week."

Government-Sanctioned Cartels II

Cartels: In Fiction I

Cartels: In Fiction II

Comparing Industries

| Industry | Firms | Entry | Price (LR Eq.) | Output | Profits (LR) | Cons. Surplus | DWL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perfect competition | Very many | Free | Lowest (MC) | Highest | 0 | Highest | None |

| Monopolistic competition | Many | Free | Higher (p>MC) | Lower | 0 | Lower | Some |

| Oligopoly (non-cooperative) | Few | Barriers? | Higher | Lower | Some | Lower | Some |

| Monopoly1 (or cartel) | 1 | Barriers | Highest | Lowest | Highest | Loweset | Largest |

1 Without price-discrimination. Price-discrimination will increase output, increase profits, decrease consumer surplus, decrease deadweight loss

Contestable Markets

Is Monopoly a Nash Equilibrium?

Now that we understand Nash equilibrium...

Are outcomes of other market structures Nash equilibria?

Is Monopoly a Nash Equilibrium?

Now that we understand Nash equilibrium...

Are outcomes of other market structures Nash equilibria?

Perfect competition: no firm wants to raise or lower price given the market price ✓

Is Monopoly a Nash Equilibrium?

Now that we understand Nash equilibrium...

Are outcomes of other market structures Nash equilibria?

Perfect competition: no firm wants to raise or lower price given the market price ✓

Monopolist maximizes π by setting q∗: MR=MC and p∗=Demand(q∗)

- This is an equilibrium, but is it the only equilibrium?

- We've assumed just a single player in the model

- What if customers refuse to pay p>MC?

- What about potential competition?

Contestable Markets I

- Model the market as an entry game, with two players:

Incumbent which sets its price pI

Entrant decides to stay out or enter the market, setting its price pE

- Price competition between the two firms with similar products1 ⟹ consumers buy only from the firm with the lower price

1 In the canonical economic models of oligopoly,

this is known as "Bertrand competition."

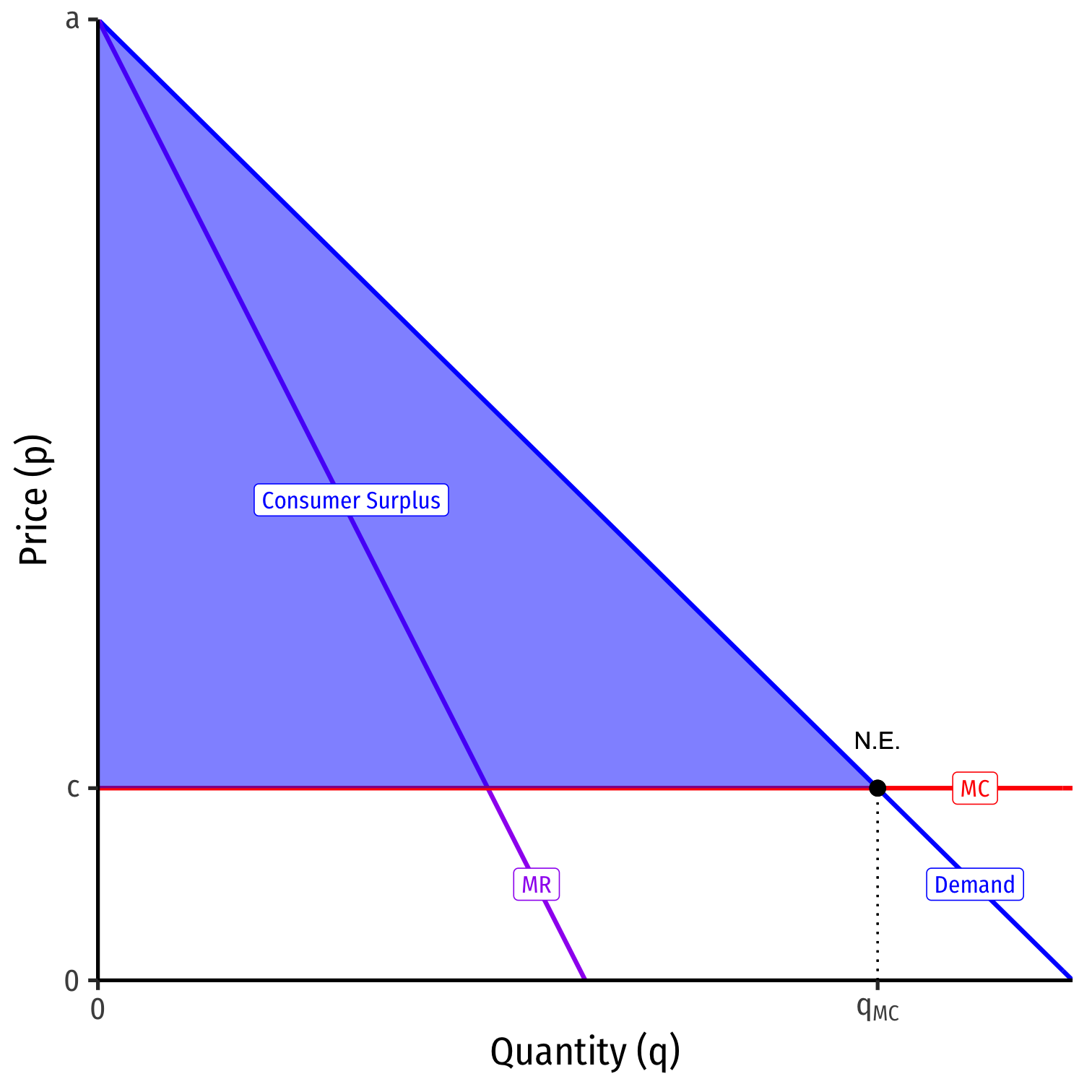

Contestable Markets II

Suppose firms have a total cost of C(q)=cq

- Thus, a marginal cost of MC(q)=c

If Incumbent sets pI>c, then Entrant would enter and set pE=pI−ϵ (for arbitrary ϵ>0)

Contestable Markets II

Suppose firms have a total cost of C(q)=cq

- Thus, a marginal cost of MC(q)=c

If Incumbent sets pI>c, then Entrant would enter and set pE=pI−ϵ (for arbitrary ϵ>0)

- Incumbent would forsee this, and try to price lower than pE

- undercutting continues until...

Contestable Markets II

Suppose firms have a total cost of C(q)=cq

- Thus, a marginal cost of MC(q)=c

If Incumbent sets pI>c, then Entrant would enter and set pE=pI−ϵ (for arbitrary ϵ>0)

- Incumbent would forsee this, and try to price lower than pE

- undercutting continues until...

Nash Equilibrium: incumbent sets pI=c, no entry

- A single firm, but the competitive outcome!

- p∗=MC, π=0

- competitive q∗

- max Consumer Surplus, no DWL

Contestable Markets II

Suppose firms have a total cost of C(q)=cq

- Thus, a marginal cost of MC(q)=c

If Incumbent sets pI>c, then Entrant would enter and set pE=pI−ϵ (for arbitrary ϵ>0)

- Incumbent would forsee this, and try to price lower than pE

- undercutting continues until...

Nash Equilibrium: incumbent sets pI=c, no entry

- A single firm, but the competitive outcome!

- p∗=MC, π=0

- competitive q∗

- max Consumer Surplus, no DWL

Contestable Markets II

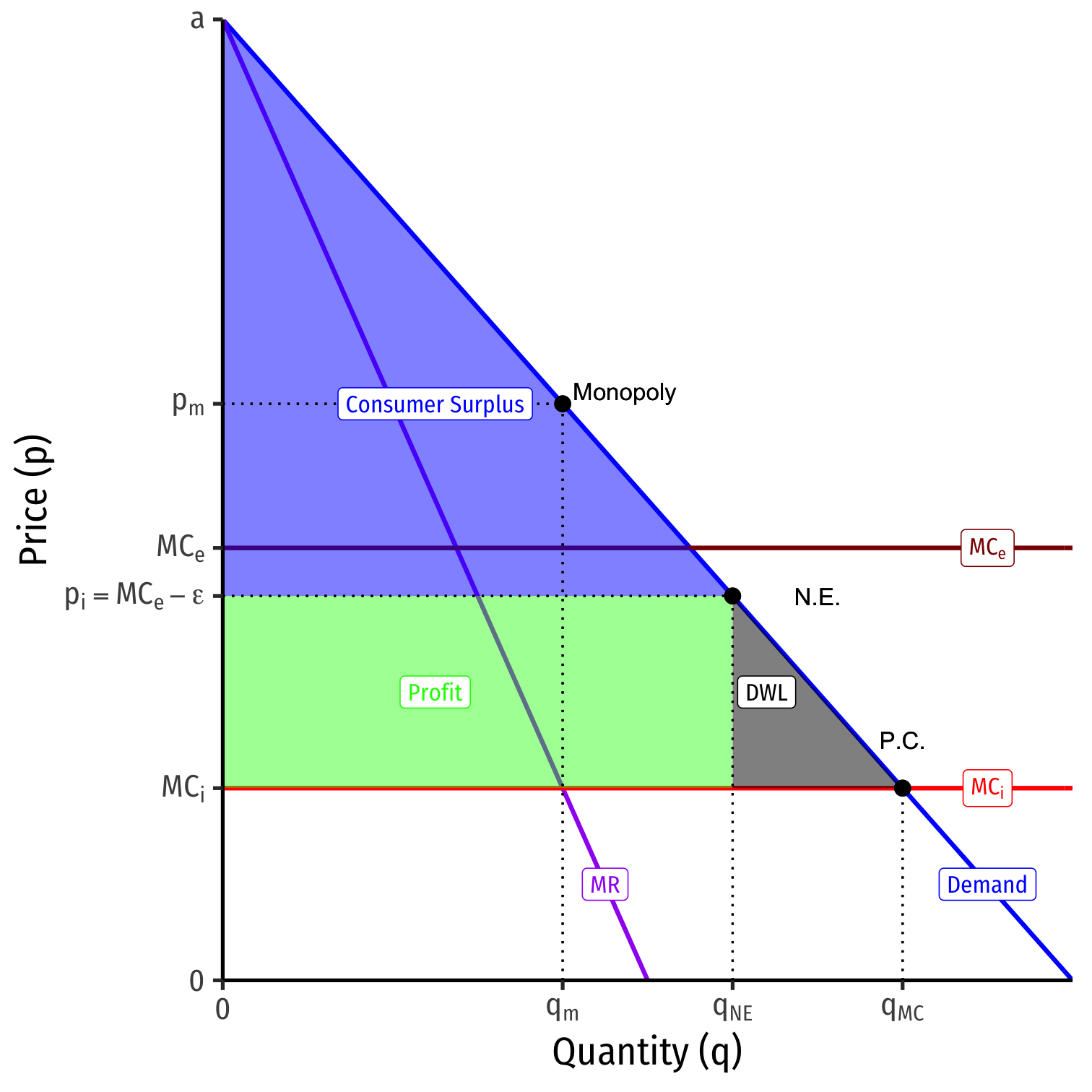

- What if the entrant has higher costs than the incumbent: cE>cI?

Contestable Markets II

What if the entrant has higher costs than the incumbent: cE>cI?

Nash equilibrium: incumbent sets pI=pE−ϵ

- Entrant stays out

A monopoly, but not the worst case

Contestable Markets II

What if the entrant has higher costs than the incumbent: cE>cI?

Nash equilibrium: incumbent sets pI=pE−ϵ

- Entrant stays out

A monopoly, but not the worst case

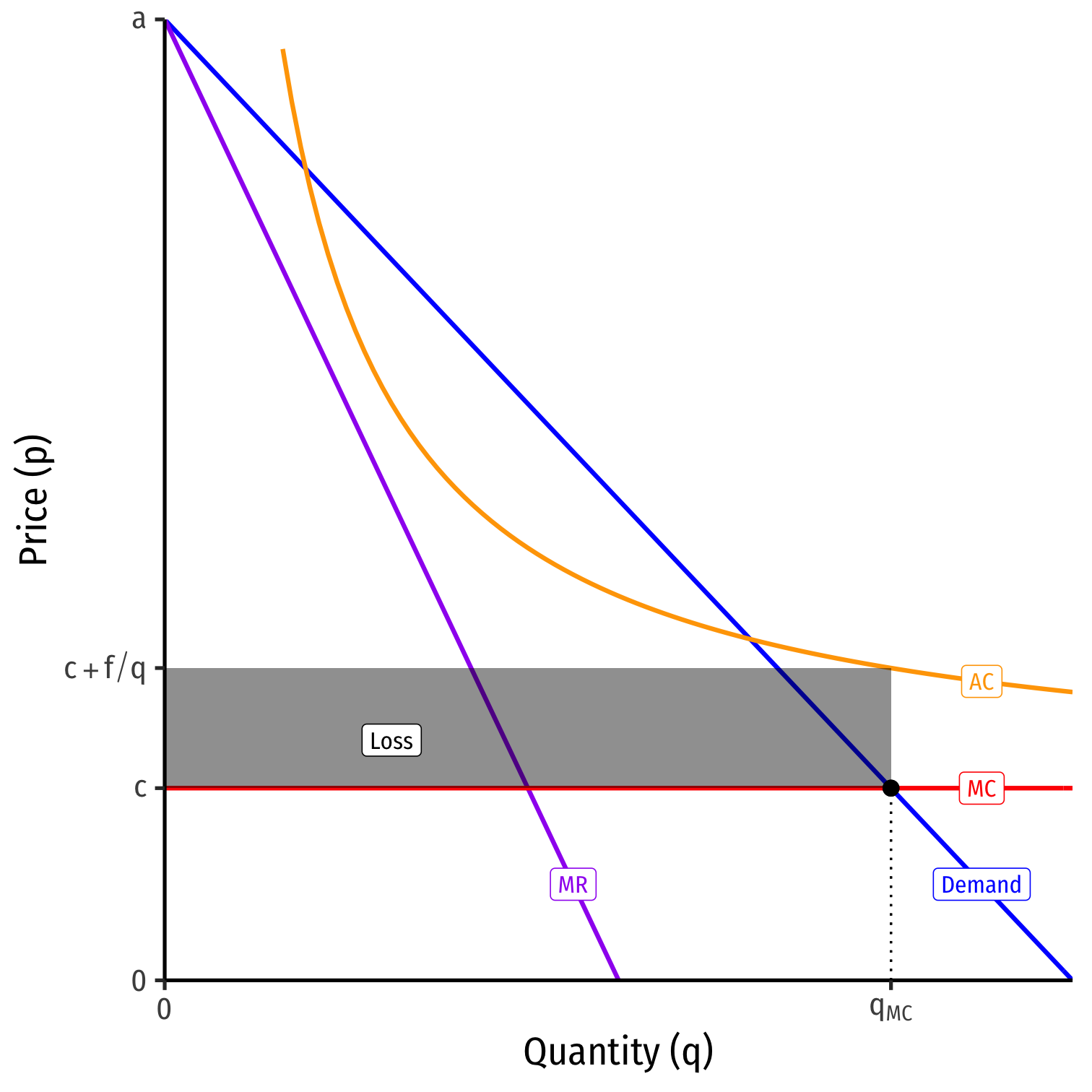

Contestable Markets III

Suppose firms have the same cost structures again

What if there are fixed costs, f?

- C(q)=cq+f

- MC(q)=c

- AC(q)=c+fq

Economies of scale prevent marginal cost pricing from being profitable

- π=−fq<0

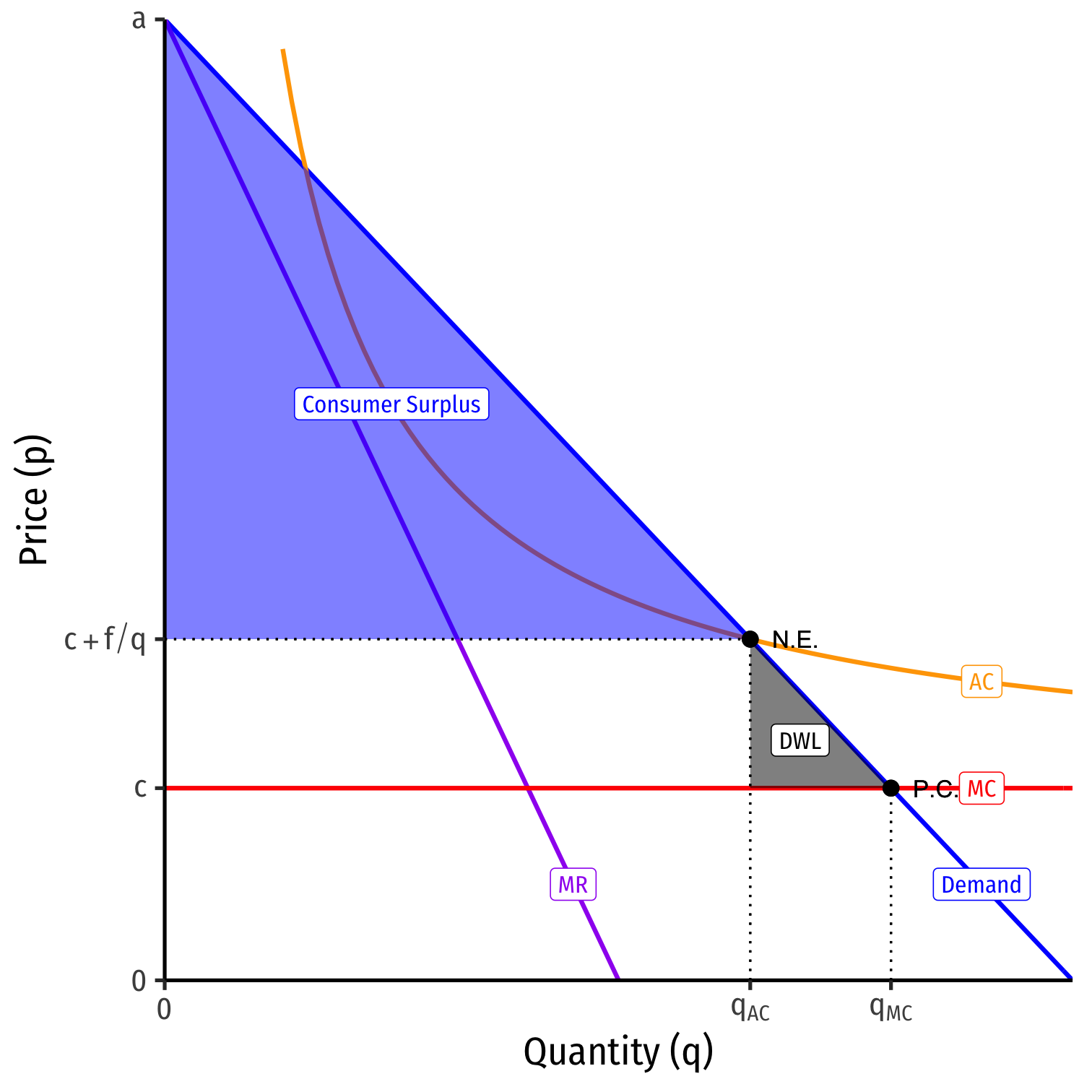

Contestable Markets IV

Nash equilibrium: Incumbent prices at pI=AC earns π=0

Entrant stays out

Again, "monopoly" but earning no profits, and not as bad as pure monopoly

What About Sunk Costs? I

Fixed costs ⟹ do not vary with output

If firm exits, could sell these assets (e.g. machines, real estate) to recover costs

- Thus, "hit-and-run" competition remains potentially profitable

- Maintains credible threat against incumbent acting as a monopolist

What About Sunk Costs? I

- But what if assets are not sellable and costs not recoverable - i.e. sunk costs?

- e.g. research and development, spending to build brand equity, advertising, worker-training for industry-specific skills, etc

What About Sunk Costs? II

These are bygones to the Incumbent, who has already committed to producing

But are new costs and risk to Entrant, lowering expected profits

In effect, sunk costs raise cE>cI, and return us back to the second example

Nash equilibrium:

- Incumbent can deter entry with pI=pE−ϵ

- Inefficient, p>AC, but again not as bad as pure monopoly

Contestable Markets: Recap

Markets are contestable if:

- There are no barriers to entry or exit

- Firms have similar technologies (i.e. similar cost structure)

- There are no sunk costs

Economies of scale need not be inconsistent with competitive markets (as is assumed) if they are contestable

Generalizes "prefect competition" model in more realistic way, also game-theoretic

Contestable Markets: Summary

William Baumol

(1922--2017)

"This means that...an incumbent, even if he can threaten retaliation after entry, dare not offer profit-making opportunities to potential entrants because an entering firm can hit and run, gathering in the available profits and departing when the going gets rough."

Baumol, William, J, 1982, "Contestable Markets: An Uprising in the Theory of Industry Structure," American Economic Review, 72(1): 1-15

Summary of the Course and Reminder

- Recall: models ≠ reality

- Models help us understand a complex reality

...In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it. The following Generations, who were not so fond of the Study of Cartography astheir Forebears had been, saw that that vast Map was Useless...

Jorge Luis Borges, 1658, On Exactitude in Science